The US Military Since The Korean War

American sovereign independence began with defense, yet since the Korean War has increasingly transformed into the global declaration of militarization apart from Congress seen today, as America moves beyond the Global War on Terror (GWOT.) The Korean War started June 25th, 1950, acting as the pivotal fulcrum between properly legislated Constitutional warfare and a new breed of future undeclared wars initiated by the Executive Branch. The Korean War began in 1950, yet due to the Cold War and the Soviet Union’s alliance with Northern Korea above the 38th Parallel, the United States wars remained undeclared due to fears of kindling a Third World War, as it sent troops into battle[1] (NEH). The Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the Global War of Terror (GWOT), far diverted America from its obligation to invoke and abide by Constitutional procedure, while functioning without a solid clearly formulated and absolute objective. This was necessary during the Korean and Vietnam War, however allowed its criteria to change over time, at the Military’s discretion.

Without Congressional voting, and a formal declaration, our servicemen and women’s voices, nor the voices of U.S. civilians, lack influence over the interests of U.S. foreign policy. This allows the government to exert international force, injecting themselves into foreign civil wars throughout nations on the other side of the globe. What began as reactions to attacks on our individual American way of life, has now transformed to the proactive prediction of potential hostile threats through foreign governments around the world. Allowing Congress the Constitutional privilege to vote on a formal declaration of war with the goal of fulfilling a particular [mutually agreed upon] legislative action would inherently boost morale within troops and civilians, leading to a more collectively supportive, and likely more successful, outcome. However, the trend which was set during the Cold War with the Soviet Union has transformed the modern state of foreign affairs in which our nation resides. Rather than defend the interests of our nation, the focus of our military post-1950 has deferred to the interests of global institutions like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the United Nations (UN).

Constitutional Analysis

Our nation’s Founder’s thoughtfully drafted our U.S. Constitution, specifically creating Article I, Section 8.11[2] (Archives). In this [seemingly forgotten] section, our Constitution grants Congress the absolute power to declare war. According to the United States Senate, this power has only been utilized eleven times throughout the course of our national history. Yet beyond those eleven declarations, lies a controversial diversion to our Constitutional foundation. Beginning in the Korean War, the President, and the Military itself, gained the power to engage in global warfare at will. Rather than reacting to an attack, American began to proactively engage in war with rising evil around the world, to prevent future Hitlerian-like dictators. The Constitution’s Article I, Sections 8.13 and 8.14 grant Congress powers to provide and maintain a Navy, while making rules for the government and regulation of land and Naval Forces. Constitution’s Article I, is Section 10.3 is perhaps the most relevant yet neglected section, which states “No State shall, without the Consent of Congress…enter into any Agreement or Compact…with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.” The Cold War brought heighten fears of an atomic escalation with the Soviet Union, the American government and military-industrial complex remained reluctant to abide by their traditional Constitution limitations. Today, this trend of hesitancy and conscious neglect remains consistent.

The Declared Wars (WWI, WWII)

President Woodrow Wilson requested Congress enact a formal declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd 1917. President Wilson’s request would be granted two days later, beginning World War I. This represented the fourth official Congressional declaration of War in American history[3] (United States Senate). The U.S. Military entered WWI with high morale and a sense of purpose, backed by the support of the nation. Riding a wave of victory delivered from the Spanish-American War, troops entered the global conflict. Citizen morale remained at an all-time high. The classic “I Want YOU For the U.S. Army” enlistment poster made its first appearance[4] (Si). Others proclaimed the message to “Fight or Buy Bonds,” telling Americans to fight or contribute their own currency to fund the cost of war. World War I represented the unification of both American citizens and the military to become one united force.

America entered World War II on December 7th, 1941, following the attack Pearl Harbor. Despite the surprise attack to our troops, morale remained high following the success of the past two formal declarations of war through Congress[5] (LOC). As the U.S. Military entered battle to defend America and our Allies, the nation rallied behind the cause, awaiting the return of our war heroes. One of the many factors which ensured the success of our U.S. troops during World War II was the collective support of the people to meet the financial needs of the military. As reported by journalist I.F. Stone on December 27th, 1941, “When wars are fought with tanks and planes, defeat or victory is decided on the assembly line[6],” (Stone, I.F., 1988, 95). After the December 7th [1941] attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. Congress promptly and unanimously declared war on Japan, creating a domino effect. Congress’s formal declaration of war against Japan, triggered Germany to fulfill its conditional obligation to uphold support for their ally. In reaction, Germany declared war upon the United States on the morning of December 11th, 1941, as documented by the U.S. House of Representatives[7]. Congress enacted war against Italy that same day, marking our eighth official declaration of war as an American nation, recorded by the U.S. Senate[8]. Congress would declare further wars against Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania would follow as the ninth, tenth, and eleven formal declarations throughout American history[9] (Senate). The House of Representatives states that “[t]he House first adopted the war resolution against Germany 393–0, followed moments later by a 399–0 vote to declare war on Italy.” The Senate voted 88-0, in favor of a declaration of war with Germany, and 90-0 in favor of a formal war against Italy.

The Undeclared Wars

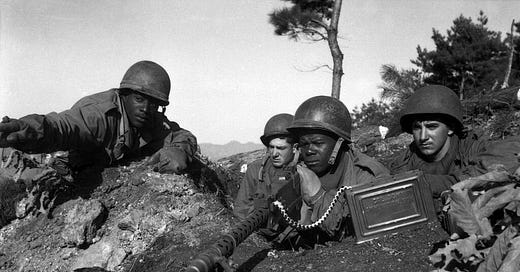

On June 25th, 1950, the Korean War began[10] (Eisenhowerlibrary). Despite many strategic planners suffering from “victory disease,” the undeclared war against North Korean Communist forces did not receive the same national attention. Robert F. Ritchie records[11], “Meanwhile some of the most experienced soldiers on Earth moved into North Korea, crossing the Yalu. Overconfident and suffering a bit from ‘victory disease,’ MacArthur moved north in what Geoffrey Perret called ‘diverging columns’” (Ritchie, R. F. 2021, 142.) The Korean War represented the first military engagement apart from Congress, and set the standard for military engagement without an official and clearly mapped objective.

According to the United Nations Command (UNC), established on July 7th, 1950, the “ UNC signifies the world’s first attempt at collective security under the United Nations system[12].” Without the focused national support of Congress and U.S. civilians, the Korean War relied not on a single objective, but a globally transformative one. What began as President Harry S. Truman’s decimation of Communism, soon shifted into its containment, while securing Seoul. Had the United States formally declared war upon North Korea, it may have worked, permanently eradicating communism from Korea. The Soviet Union detonated their first atomic bomb just one year earlier in 1949, adding great determent to engaging in formal conflict[13] (Osti). This hesitation to declare war, to avoid an escalating conflict, forced our military’s definition of “victory” to shift, ultimately setting the tone for the standard of our future global warfare. The reason the Korean War remained undeclared by Congress, was fears that Korean allies [China and the Soviet Union] would feel that same obligation seen in Germany that facilitated World War II. In the height of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, America did not want to further escalate the cold war into a hot war. Americans fought against the Soviet Army during the Korean War, however an official declaration would have resulted in further soviet aggression. As documented by Historian Donald Jeffries, our engagement in “Korea paved the way for our disastrous involvement in Vietnam with more limited goals indecipherable enemies and massive casualties” (Jeffries, D., 2019, 326).

On August 7th, 1964, U.S. President Lydon B. Johnson (LBJ) signed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution[14] (Archives). The Tonkin Gulf Resolution [informally] meant war. Section 2 of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution states that “[t]he United States regards [the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia] as vital to its national interest and to world peace.” The Tonkin Resolution also added that the United States was prepared to “take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member…of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty requesting assistance in defense of its freedom.” Without an official declaration, the United States could once again resist Soviet Aggression, especially following the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962[15] (State). In many ways, this “moment when the two superpowers came closest to nuclear conflict” marked the pinnacle of the Cold War. This meant that the United States needed to again avoid the formalities associated with war, taking into consideration the allies of North Vietnam’s Communist regime. This was a rational move, allowing us to avoid even greater casualties.

The Vietnam War resisted a formal declaration before Congress, representing the same geopolitical opportunity to prevent an escalation in global conflict. The Vietnam War represented America’s second informal international military engagement and sought to avoid the traditional authority of the Constitution, tiptoeing around a cold war escalation into a full-fledged nuclear war. Weapons of Mass Destruction [WMD] are sustained today, as a factor in the decision to continue to avoid formal declarations. In Vietnam, if a formal war had been declared, the Soviet Union would have been forced to declare war on the United States, as Germany did in response to our declaration on Japan in WWII. This was the right decision, as the Soviet Union was itself founded by criminals, and as such the Soviet regime would not have abided by the standards of limited warfare. To avoid a potential global conflict and catastrophic nuclear future, the United States was forced to remain informally undeclared as it entered war.

Today this has become the trend to “ensure global democracy,” bringing the United States of America into a state of “new world order” known globally as “Pax Americana[16],” Latin for “American Peace.” Functioning as a dual edge sword, this omission has not guaranteed viable foreign policy. The Executive Branch has taken control of U.S. foreign policy without the involvement of Congress. These policies remain segregated from the decisions of the very servicemen and women sent into battle, and the support of the American people.

The 1980s continued US interests and involvement in foreign policy drifted America further away from its national security and deeper into international alliances. This meant American military servicemen and women being sent into combat to defend the interests of foreign nations. This included Operation Eagle Claw[17] in Iran in 1980 and Operation El Dorado Canyon[18] in Libya in 1986. The Gulf War of the 1990’s continued this advancement, abandoning traditional American declarations of war, in exchange for avoiding nuclear escalations, and upholding peace (by NATO’s standard), in order to sway the outcome of international conflict. As stated by Historian Robert F. Ritchie[19], “Desert Shield protected America’s vital ally Saudi Arabia from Saddam Hussein’s invading army, but to liberate Kuwait, Desert Storm would need to be launched,“ (Ritchie, R. F., 2021, 180)

Operation Desert Shield began on August 7nd, 1990, just five days after dictator Saddam Hussein ordered the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait[20] (Army). This represented the first American engagement in international war after the decline of the Soviet empire. The Cold War would officially end with the dissolvement of the Soviet Union in 1991[21] (Truman).

Operation Desert Storm’s UN-led coalition allowed the US to avoid direct responsibility. Official air and ground war began on January 17th, 1991, ending on February 28th, 1991[22],[23] (State, Army). Instead of formally laying out clear objectives, approved by Congress, General Colin Powell noted a similar strategy to the Korean War “Our strategy to go after this [Iraqi] army is very simple. First we’re going to cut it off, and then we’re going to kill it.” The difference from the previous wars is the term “it” presented to the public remained ambiguous, allowing a later definition to be addressed, when the time came to withdraw from the war.

The Global War on Terror saw a rise in “neo-Conservatives,” mirroring the views of the Bush Administration. As reported by Robert F. Ritchie, “To many thinkers in the neo-Conservative movement, the relatively easy victory in Afghanistan would justify war in Iraq, Syria, or just about anywhere some Hitler wannabe type seemed to threaten” (Ritchie, R. 2021, 187). Post-9/11 Americans across the nation remained glued to their home televisions sets with passion. 24/7 broadcasts aired on every news station, giving citizens real-time updates to the United States’ military response to the egregious terrorist attack on our nation. Still, American troops received no official declaration of war. As stated by Kentucky Senator Rand Paul on Wednesday, June 6, 2018, “After the attacks on September 11, 2001 (9/11), President Bush did his constitutional duty. He asked Congress to authorize war against the people who attacked us on 9/11 or anyone who harbored them or aided and abetted those who had attacked us” (Govinfo). Despite President Bush wanting more expansive legislation, however, Congress insisted on “narrowing the mandate to use force”, as Senator Paul reminds us. In the 2018 hearing, titled “War Powers and the Effects of Unauthorized Military Engagements on Federal Spending,” Senator Rand Paul added that “Authorization was specific and solely to be directed against the people who attacked us on 9/11 and anyone who helped or harbored them. Period. It is safe to say that no one in Congress believed that they were voting for a worldwide war on ‘terrorism’ in twenty some odd countries that would go on for decades.”

On March 19th, 2011, President Obama targeted Libyan dictator Muammar Ghaddafi with a Predator drone under Operation Odyssey Dawn on behalf of NATO, striking his convoy[24] (Govinfo). As a result of this attack, the local Libyan opposition captured the dictator, beating and killing him. This marked the dawn of a new age of warfare, one where the Constitution no longer played a role. Instead, the Executive Branch boldly declared its control, using unmanned aerial drones to take out dictators, rather than using the American military as seen in historic formally declared wars. As Robert Ritchie describes “The American intelligence community that had been weakened after Vietnam in its ability to employ human intelligence assets now went from a reactive to proactive search in an attempt to desperately follow any potential terror lead that might involve weapons of mass destruction (WMDs)” (Ritchie, R.F. 2021, 187).

This trend continued with Operation “Restore Hope” in Somalia in 1992, Operation Uphold Democracy in 1994, the Bosnian War in 1994, Afghanistan in 2001, the Invasion of Iraq in 2003, Pakistan in 2004, Somalia again in 2007, Operation Ocean Shield in 2009, the US-NATO assassination of Ghaddafi in 2011, the Lord’s resistance Army in 2011, and a return to Iraq in 2014[25]. (Osi). Today the undeclared war continues in Syria, Yemen, and Libya[26],[27],[28], (Jcs, Gao, WhiteHouse) .

As Robert F. Ritchie notes[29] “[t]he American military has always embodied the best aspects of American society…These servicemen and women deserve a vision clearly articulated and put into writing. They deserve leadership with the courage to vote on future actions, putting their own political futures on the line” (Ritchie, R. F., 2021, 200). Comparing various attributes before and after the Korean War reveals the changes which had occurred over the years as Wars were launched around the world without a formal declaration. This led to many contributing factors placed on each war, influencing its result. These factors included our American Way of Fighting (AWoF), our national strategy, troop morale, and international support [or a lack thereof]. The overall focus of our nation’s military changed from World War I. This most notably occurred by the immediate response to national attacks, such as the sinking of the Lusitania (WWI), and Pearl Harbor (WWII). In the Korean War, America began responding to threats before they had a chance to declare war on our nation. This was catalyzed post-9/11 when the Global War of Terror (GWOT) was launched. Since WWII, America remained in a position where it has been hesitant to formally declare wars due to external geopolitical factors, in hopes of avoiding a third World War. In many ways throughout the war, U.S. troop morale remained dependent on civilian support. Without support from the American citizens, American troops questioned their own nation’s purpose in the conflict, especially as U.S. military casualties began to add up, and strategies began to change. During World War I & II, with the support of America, soldiers, and military personnel knew what they were fighting for, returning from war home as heroes, and gaining support from their national and local communities. This was sustained by the national support from the people and American corporations, building marketing campaigns on the success of our military. The Korean War began a diversion from this expectation, many news outlets pushed Korean War stories onto the back page. Vietnam troop morale sank even lower as the American media focused on the soldiers' and personnel’s deaths, rather than our military victories. Upon their return home from battle, these men were not viewed in such a heroic light as those who served in WWI and WWII. Veterans unjustly faced domestic persecution, being branded as warmongers by American citizens.

Despite the impacts upon our nation, and the majoritarian opposition to war, God reveals to us its necessity in Exodus. While it does not advocate the offensive imperialistic murder of potential threats, it discloses the views held by the Executive Branch who engage in conflict. As the Holy Spirit reminds us in Exodus 23:24, 25 (NLT), “You must not worship the gods of these nations or serve them in any way or imitate their evil practices. Instead, you must utterly destroy them and smash their sacred pillars. You must serve only the LORD your God. If you do, I will bless you with food and water, and I will protect you from illness.” In many ways, American engagement in the destruction of dictatorships, allowed for the distribution of food and water, [among other necessities], back into the economy of the people.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, America has seen a massive transformation since the last declared war, previous to the Korean War. The Executive Branch now defends the interests of NATO, rather than America. Post-Korean War, America’s decision to engage in war has effectively moved from the civilian-elected legislative branch to the bureaucratic executive branch. The executive branch now drone strikes potential threats at will, exerting unrestricted executive privilege, instead of enacting a clear strategy through Congress.

It is the Constitutional neglect of Article I, Section 8.11 that has driven the United States servicemen and women to diligently commit themselves to wars without clear objectives. Worse, these unofficial wars feature a notoriously historical lack of official appropriations. Further, lacking official U.S. legislation has weakened troop morale, and as a result has led to [comparatively] unsuccessful outcomes, forcing the American military to shift the definition of victory to match the outcome. Should the United States of America’s definition of victory directly correlate with that which is defined by NATO and the United Nations? This question has lingered while the US contributions to conflict drifted our military’s standard from national security to global purveyor of peace. Global alliances should not come before national sovereignty. Bureaucracies should not be tasked with the prediction of evil and terror around the world, apart from Congress. The bottom line, the Constitution stands as a structural foundation for the longevity and success of our country. We must pray that in the future, servicemen and women, and God-fearing Christ-centered legislators will have a greater voice in the direction of our foreign policy and national strategies which form as a result.

Bibliography

Committee on Foreign Relations. Kerry F. John, Christopher J. Dodd, Richard G. Lugar Russell D. Feingold, Bob Corker, Barbara Boxer, Johnny Isakson, Robert Menendez, James E. Risch, Benjamin L. Cardin, Jim Demint, Robert P. Casey, Jr., John Barrasso, Jim Webb, Roger F. Wicker, Jeanne Shaheen, James M. Inhofe, Edward E. Kaufman, Kirsten E. Gillibrand, David Mckean,Kenneth A. Myers, Jr., "Exploring Three Strategies For Afghanistan." U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg55538/html/CHRG-111shrg55538.htm.

Committee on Foreign Relations. Kerry F. John, Massachusetts, Barbara Boxer, Richard G. Lugar, Robert Menendez, Bob Corker, Benjamin L. Cardin, James E. Risch, Robert P. Casey, Jr., Marco Rubio, Jim Webb, James M. Inhofe, Jeanne Shaheen, Jim Demint, Christopher A. Coons, Johnny Isakson, Richard J. Durbin, John Barrasso, Tom Udall, Mike Lee, William C. Danvers, Kenneth A. Myers, Jr. " U.S. Policy To Counter The Lord's Resistance Army." U.S. Government Publishing Office. Accessed on March 5th, 2023. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-112shrg75023/html/CHRG-112shrg75023.htm.

Committee on Foreign Relations. Paul, Rand, James Lankford, Gary C. Peters, Michael B. Enzi, Kamala D. Harris, John Hoeven, Doug Jones "War Powers And The Effects Of Unauthorized Military Engagements On Federal Spending." U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115shrg33954/html/CHRG-115shrg33954.htm.

Department of State. "Milestones: 1993–2000" Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1993-2000/haiti.

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. "Korean War | Eisenhower Presidential Library." Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home.” https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/research/online-documents/korean-war.

Garamone, Jim. "Syrian Conflict Will Take Years to Sort Out, Dempsey Says." Joint Chiefs of Staff Directory. https://www.jcs.mil/Media/News/News-Display/Article/571526/syrian-conflict-will-take-years-to-sort-out-dempsey-says/.

National Endowment for Humanities. Nye, Peter Joffre. "Korea and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel | The National Endowment for the Humanities." The Magazine of the National Endowment for Humanities Volume 40, Issue 2. (2019): https://www.neh.gov/article/korea-and-thirty-eighth-parallel.

National Institutes of Health. Guha-Sapir, Debarati, Ruwan Ratnayake. "Consequences of Ongoing Civil Conflict in Somalia: Evidence for Public Health Responses - PMC." National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine. Accessed on March 5th, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2716514/.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization. "NATO - News: NATO strikes Gaddafi forces, 09-Apr.-2011." News. (2011): https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/news_72192.htm?selectedLocale=en.

Ritchie, Robert F. 2021. Modern American Military History. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Stone, I.F. 1988. The War Years 1939-1945. United States of America: The Nation Publishing.

Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation and Trade. Royce, R. E., Christopher H. Smith, Eliot L. Engel, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Brad Sherman, Dana Rohrabacher, Gregory W. Meeks, Steve Chabot, Albio Sires, Joe Wilson, Gerald E. Connolly, Michael T. Mccaul, Theodore E. Deutch, Ted Poe, Brian Higgins, Matt Salmon, Karen Bass, Darrell E. Issa, William Keating, Tom Marino, David Cicilline, Jeff Duncan, Alan Grayson, Mo Brooks, Ami Bera, Paul Cook, Alan S. Lowenthal, Randy K. Weber Sr., Grace Meng, Scott Perry, Lois Frankel, Ron Desantis, Tulsi Gabbard, Mark Meadows, Joaquin Castro, Ted S. Yoho, Robin L. Kelly, Curt Clawson, Brendan F. Boyle, Scott Desjarlais, Reid J. Ribble, David A. Trott, Lee M. Zeldin, Daniel Donovan "Libya's Terrorist Descent: Causes And Solutions." U.S. Government Publishing Office https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg21676/html/CHRG-114hhrg21676.htm.

The United States House of Representatives. “The House Declarations of War Against the Axis Powers.” History, Art & Archives. https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1901-1950/The-House-declarations-of-war-against-the-Axis-Powers

The United States Library of Congress. “Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945 ." Classroom Materials. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/world-war-ii/.

Truman Library. “Timeline of the Cold War.” https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/TrumanCIA_Timeline.pdf.

U.S Government Accountability Office. "GAO-08-806, Combating Terrorism: Increased Oversight and Accountability Needed over Pakistan Reimbursement Claims for Coalition Support Funds." GAO Reports & Testimonies. Accessed on March 5th, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/a277247.html.

U.S Government Accountability Office. "Yemen: State and DOD Need Better Information on Civilian Impacts of U.S. Military Support to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates” GAO Reports & Testimonies. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-105988.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. "Operation Desert Shield." History. Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/dshield_dstorm/desert-shield.html.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. "Operation Desert Storm." U.S. Army Center of Military History Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/desert-storm/index.html.

U.S. Department of Defense. Endicott, Judy G. “Raid on Libya: Operation El Dorado Canyon.” U.S. Department of Defense Media. https://media.defense.gov/2012/Aug/23/2001330097/-1/-1/0/Op%20El%20Dorado%20Canyon.pdf.

U.S. Department of Defense. Russell, Edward T. “Crisis in Iran: Operation Eagle Claw.” U.S. Department of Defense Media. https://media.defense.gov/2012/Aug/23/2001330106/-1/-1/0/Eagleclaw.pdf.

U.S. Department of State. "U.S. Relations With Bosnia and Herzegovina - United States Department of State." U.S. Relations With Bosnia and Herzegovina Fact Sheet. https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-bosnia-and-herzegovina/.

U.S. National Archives. "Tonkin Gulf Resolution (1964).” Archives. Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/tonkin-gulf-resolution.

United Nations Command. “History of the Korean War.” https://www.unc.mil/History/1950-1953-Korean-War-Active-Conflict/.

United States Coast Guard. "Pax Americana." The Future’s Group. https://www.uscg.mil/Portals/0/Strategy/Scenario%20Pax%20Americana.pdf.

United States Department of State. Kelly, Thomas. "The U.S. Government's Approach to Countering Somali Piracy." Remarks at Combating Piracy Week. (2012): https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/pm/rls/rm/199929.htm.

United States Senate. "U.S. Senate: About Declarations of War by Congress." Senate Historical Documentation. https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/declarations-of-war.htm.

United States Whitehouse. Biden, Joseph R. Jr. "Notice on the Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Libya | The White House." Whitehouse Briefing Room. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/02/17/notice-on-the-continuation-of-the-national-emergency-with-.

[1] NEH. "Korea and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel” The National Endowment for the Humanities. Accessed on March 4th, 2023. https://www.neh.gov/article/korea-and-thirty-eighth-parallel.

[2] Archives. "The Constitution of the United States" National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript.

[3] Senate. “About Declarations of War by Congress.” Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/declarations-of-war.htm.

[4] Si. "Rallying Support for the War Effort (WWI) | Smithsonian Institution." Si. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/promoting-the-war-effort.

[5] LOC. "Great Depression and World War II" Loc. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/world-war-ii/.

[6] Stone, I.F. 1988. The War Years 1939-1945. United States of America: The Nation

[7] House. “The House Declarations of War Against the Axis Powers.” https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1901-1950/The-House-declarations-of-war-against-the-Axis-Powers/.

[8] Senate. “Declaration of War with Italy, WWII (S.J.Res. 120).” https://www.senate.gov/about/images/documents/sjres120-wwii-italy.htm.

[9] Senate. "U.S. Senate: About Declarations of War by Congress." Senate. https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/declarations-of-war.htm.

[10] Eisenhowerlibrary. "Korean War." https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/research/online-documents/korean-war.

[11] Ritchie, Robert F. 2021. Modern American Military History. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

[12] UNC. “History of the Korean War.” https://www.unc.mil/History/1950-1953-Korean-War-Active-Conflict/.

[13] Osti. "Manhattan Project: Nuclear Proliferation, 1949-Present." Osti. Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945-present/proliferation.htm.

[14] Archives. "Tonkin Gulf Resolution" National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/tonkin-gulf-resolution.

[15] State. "Milestones: 1961–1968 - Office of the Historian." History. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/cuban-missile-crisis.

[16] USCG. "Pax Americana." United States Coast Gaurd. Accessed on March 4th, 2023, https://www.uscg.mil/Portals/0/Strategy/Scenario%20Pax%20Americana.pdf.

[17] Defense. “Crisis in Iran: Operation EAGLE CLAW.” Accessed March 5th, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2012/Aug/23/2001330106/-1/-1/0/Eagleclaw.pdf.

[18] Defense. “Raid on Libya: Operation ELDORADO CANYON.” Accessed March 5th, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2012/Aug/23/2001330097/-1/-1/0/Op%20El%20Dorado%20Canyon.pdf.

[19] Ritchie, Robert F. 2021. Modern American Military History. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

[20] Army. "Operation DESERT SHIELD.” U.S. Army Center of Military History. https://history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/dshield_dstorm/desert-shield.html.

[21] Truman. “Timeline of the Cold War” Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/TrumanCIA_Timeline.pdf

[22] State. "Milestones: 1989–1992 - Office of the Historian." History. Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1989-1992/gulf-war.

[23] Army. "Operation DESERT STORM. ” U.S. Army Center of Military History." Accessed on March 1st, 2023. https://history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/desert-storm/index.html.

[24] Govinfo. "Libya's Terrorist Descent: Causes And Solutions." Govinfo. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg21676/html/CHRG-114hhrg21676.htm.

[25] Osi. "Looking Back: Operation RESTORE HOPE – OSI Operations in Somalia.” https://www.osi.af.mil/News/Features/Display/Article/3252629/looking-back-operation-restore-hope-osi-operations-in-somalia/.

[26] Jcs. "Syrian Conflict Will Take Years to Sort Out, Dempsey " Joint Chiefs of Staff. Accessed on March 5th, 2023. https://www.jcs.mil/Media/News/News-Display/Article/571526/syrian-conflict-will-take-years-to-sort-out-dempsey-says/.

[27] Gao. "Yemen: State and DOD Need Better Information on Civilian Impacts of U.S. Military Support to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates | U.S. GAO." Gao. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-105988.

[28] Whitehouse. "Notice on the Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Libya | The White House." Whitehouse. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/02/17/notice-on-the-continuation-of-the-national-emergency-with-respect-to-libya-3/.

[29] Ritchie, Robert F. 2021. Modern American Military History. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing.