Licensing and Other Barriers to Competition

Modern transportation and lodging innovation ideas produce an advocation of utility and convenience backed by the public. Less personal effort and affordable competitive prices means more consumer appeal; thus more revenue. This leads to an abundance of companies following a similar structure, to the extent thereby producing its own economic system: the sharing economy.

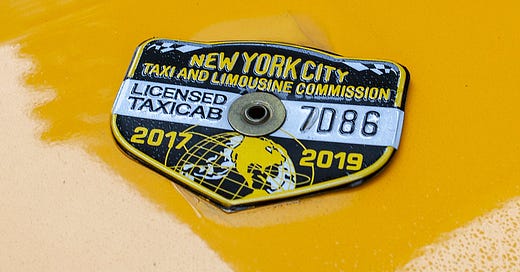

The sharing economy relies on the free market for its services and prices. As government cannot regulate a free market; it instead opposes the expansion of the unregulated economy, often declaring it competition; or unrecognized altogether. The result is the formal public rejection of unregulated private services, like transportation and lodging. One example is New York City’s Taxi & Limousine Commission notes that “[t]axicabs are the only vehicles that have the right to pick up street-hailing and prearranged passengers anywhere in New York City,” (NYC.gov). To compete with the sharing economy, concerns over safety and costs are promoted by the government.

The sharing economy defies the government’s monopolization of specific sectors, like transportation services, lodging, parking, rentals, or food delivery. Further, the sharing economy creates new jobs, giving companies the freedom to form their own prices, services, and hours of operation. Roger Miller notes that “[t]he competition from Uber has not just reduced the market value of New York taxi medallions by 40 percent. It has also made it much easier to get around New York,” (Miller, R., p. 128). Miller concludes that, “despite the best efforts of those who hate the competition, consumers so far seem to be getting the best of this one,” (Miller, R., p. 128). But these statistics needn’t be the focus of the comparison between the two; instead the convenience and utility presented to the customer is a far more viable weight of authority. In the case of sharing, the positives greatly oughtweigh the negatives. Specifically, subcategorizing each into its own brief analysis:

The Positives

The sharing economy provides jobs for the working-class, and passive income for everyday citizens. It encourages use of available excess personal resources for profit, while benefiting customers. Companies like Uber employs “more than 7 million monthly drivers and couriers on the Uber platform around the world,” (Uber). The company adds that “[u]nlike many riders and consumers who pop in and out, the amount of time they spend on the app is measured in hours and days – not minutes,” (Uber). Uber allows drivers to work on their own time, rather than establishing a fixed set of hours. In accordance with Uber’s work-on-demand feature; Scripture reminds us to “[r]emember this: Whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows generously will also reap generously,” (2 Corinthians 9:6; NIV).The sharing economy is more than an investment of resources, but also an investment of time. Therefore, its benefits rely on the availability of its distributors, hosts, or drivers.

Private companies like Airbnb cater to the host. Airbnb first offers host damage protection whereby hosts are able to recover up to $3 Million in the event of damages, (Airbnb). Secondly, it offers host liability insurance protecting customers in the “unlikely event” that any host may be “found legally responsible for a guest being hurt or their property being damaged or stolen during an Airbnb stay,” (Airbnb). This allows Airbnb hosts to rent their property at market value of government subsidized lodging. Airbnb current holds over 8 million listings on its platform; in over 100,000 cities and towns; with listings in over 220 regions and countries; and has served over 2 Billion customers, (Airbnb). Airbnb charges a 14-16% fee from the listing; either by host fee, directly paid by host; or by customer fee, split between the customer and host, (Airbnb). Similarly, with Uber, “[n]one of these drivers work for Uber itself, but the company certifies the drivers and takes 20 percent of the fares to cover its costs,” (Miller, R., p. 128).

The Negatives

Private companies within the sharing economy are not standardized. Customers often utilize multiple services for a single product, interchanging Uber and Lyft; or Seamless, GrubHub, Post Mates, Door Dash, Uber Eats; depending on their experiences. Should a ride be unbearable or a meal arrive cold, the customer is far more likely to try another service altogether. Yet, with a surplus of companies comes a lack a standardization, alongside privacy and safety concerns. Every customer must submit to data collection; private companies are free to obtain and sell personal information for profit at the customer’s expense, heightening the risk of fraud. But these foreseeable detriments are not greater than the sharing economy’s benefits to society and the posterity of the free market. Government subsidized services incur the same level of risk. The preclusion of any negative detriment in the sharing economy can be remedied by proper stewardship of resources, regulations, and liberty unto the host, driver, or provider.

Stewardship. The sharing economy’s foundation is stewardship. Other sharing economy products like MonkeyParking, a service that works with hotels to monetize vacant parking spaces, can provide revenue up to $400 and offer flexible month to month subscriptions, (MonkeyParking). Although these private companies operate outside of government regulation, they must cater to the expecations of their stakeholders. Prosper Marketplace is backed by leading investors, (Prosper). Prosper must focus its process objectives toward the achievement of the company’s stated outcome objective. This provides customers an assurance that the private institutions, like eBay, Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Seamless, GrubHub, Zipcar, and others have a consistent target goal while accountable to ethical obligation and the court of public opinion.

Christians are obligated to steward the resources God has provided them. In the New Testament the Apsotle Paul reminds us “[d]on’t neglect to do what is good and to share, for God is pleased with such sacrifices,” Hebrews 13:16 (CSB). Sharing is a natural function intended by God. As “John [the Baptist] replied ‘If you have two shirts, give one to the poor. If you have food, share it with those who are hungry.’” (Luke 3:11, NLT). Paul writes the same message to the city of Corinth, scribing is his second epistle “[e]ach one must do just as he has purposed in his heart, not grudgingly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver,” (2 Corinthians 9:7; NASB). But giving requires stewardship. It was Peter who scribed of the stewardship of our God given gifts and resources; “[a]s each has received a gift, use it to serve one another, as good stewards of God’s varied grace,” (1 Peter 4:10; ESV). Yet, it also requires safety and regulation.

Safety and Regulation

Ride share services like Uber are not immune from regulation. Uber attests that “[t]ransportation network companies (TNCs) like Uber operate in a highly regulated sector. The scope of our local regulators varies greatly depending on the market where we operate,” (Uber). To be authorized, every taxi undergoes a government regulated process. This includes gaining a medallion, licensed by the state for one year, (NYC.gov). New York City’s Taxi & Limo “[b]y law, there are 13,587 taxis in New York City and each taxi must have a medallion affixed to it. Medallions are auctioned by the City and are transferrable on the open market by licensed brokers,” (NYC.gov). Medallion brokers are licensed by the State. Similarly, Uber notes that “[b]efore anyone can drive with Uber, they must undergo a multi-step safety screen, including being checked for impaired driving and violent offenses. In addition, Uber rescreens drivers at least every year and uses technology to look for issues in between,” (Uber). While Taxi cab medallion numbers allow for identification in the event of an emergency, Uber matches its safety, directing its customers to “call 911 from the Uber app,” (Uber). This app feature provides the customer’s “live location and trip details,” to “share them with the emergency dispatcher,” (Uber). Further, Uber notes its continuance of updating safety procedures, writing in a September 2024 report that “[a]ll riders will have their account information checked against trusted third-party databases or have the option to upload an ID. Once verified, they will receive a ‘Verified’ badge,” (Uber). Here, customers benefit as “hundreds of improvements to the app” have been implemented since the company’s inception “to help keep drivers safe,” (Uber). Uber’s CEO Dara Khosrowshahi declares the company’s focus is “[h]elping to make driving and delivering safer, fairer, and easier,” (Uber). Here, the drivers must submit to these standardization in order to meet both the customer and company expectations.

Uber has its own community guidelines, prioritizing driver and rider safety. On drivers, Uber vows that “[i]f a driver reports a rider for rude or inappropriate behavior, we’ll soon send the rider a warning and tips from real drivers on how they can improve for their next ride,” (Uber). Moreover, Uber reserves the right to auto-un-match or block riders who receive low ratings from drivers, (Uber).

Conclusion

The benefits of these independent private companies outweigh the costs of its lack of regulation. Private companies are bound by the expectations of their stakeholders, and still subject to many government regulations. Moreover, the sharing economy provides jobs; offers competitive pricing; and contributes to boosting the economy, thereby lowering inflation and allowing citizens to experience a quality life. The sharing of resources is a Biblical provision, yet as with all things, is voluntary; here, eased by financial compensation. Despite the risk of fraud, lack of standardization between service providers; unregulated data collection; and other risks—the sharing economy is convenient. Though the government loses, the people benefit. Yet, as Americans we must ask ourselves the purpose of government, if not the fortification of its citizens. The sharing economy is conducive to both natural law, and to a thriving capitalist system. The natural system of the free market will self-regulate in accordance with the supply and demand of the citizenry, unlike the curation of economy formulated by government like public transportation or other subsidized services. The sharing economy relies on the outcome objective of its shareholders, concurrent with the goals of its hosts, drivers, and providers; thereby providing a quality product and experience to the consumer.

Bibliography

Airbnb. (Accessed on November 12th, 2024). Aircover. https://www.airbnb.com/help/article/3142/

Airbnb. (Accessed on November 12th, 2024). About Us. https://news.airbnb.com/about-us/

Airbnb. (Accessed on November 12th, 2024). Airbnb Service Fees. https://www.airbnb.com/help/article/1857#:~:text=Host%20fee,hosts%20with%20listings%20in%20Italy

MonkeyParking. (Accessed on November 14th, 2024). https://www.monkeyparking.co/

Prosper. (Accessed on November 12th, 2024). About. Prosper. https://www.prosper.com/about

Uber. (Accessed on November 12th, 2024). Newsroom. https://www.uber.com/newsroom/onlyonuber24/

Uber. (Accessed on November 12th, 2024). Safety. Uber. https://www.uber.com/us/en/safety/